Once, a long time ago, I was part of an indie-film forum and we were doing a light-hearted roast for the forum's founder on his birthday. I made the joke that he "didn't know the difference between being independent and being unwanted."

I didn't know how prescient I was being back then, in my naive youth.

But first, a little history.

The big studios that we know and love today, were founded by the original independent filmmakers.

Yep, that's true.

The massive conglomerates that crush all who challenge their dominance, were once a collection of small, hard-scrabble indie filmmakers fighting against a massive conglomerate that dominated the fledgling movie industry.

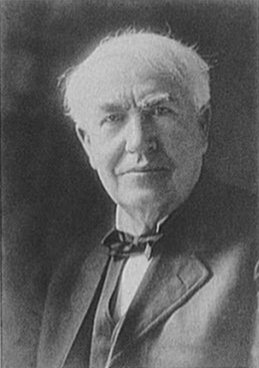

Thomas Edison, not only invented the light bulb, but patented some of the first modern motion picture cameras and projectors. Now most people would think that they're patent, gave them the right to manufacture the cameras and projectors.

Edison saw it differently.

He believed that owning the patent on the means of making films, gave him ownership of the films themselves. So all motion pictures had to be produced by the member companies of the Motion Picture Patent Company (AKA MPPC or The Edison Trust).

Anyone who tried to make their own films could face lawsuits, injunctions, and sometimes vandalism by MPPC operatives.

Some folks didn't much care for this and started heading away from the original film centres of New York and New Jersey, and went west. The founders of what would become Paramount Pictures, were planning to set up their operations in New Mexico, but changed their mind en-route and chose a little town in southern California named Hollywood. Soon others followed suit, and a new film community was born.

These tough little indies soon defeated the MPPC. Partially through anti-trust legal arguments, but mostly by beating them at their own game.

These tough little indies soon defeated the MPPC. Partially through anti-trust legal arguments, but mostly by beating them at their own game.One of the MPPC's favourite tactics was to use uncredited actors. They feared that anyone who became popular would naturally become more expensive. Now that is a reasonable concern, but a real star who put bums in seats could also be a worthwhile investment. The upstarts in Hollywood started giving credit to their actors and using the image and charisma of their more popular stars to promote films.

Another way they defeated the beast was by catering to popular tastes. The companies of the MPPC had quickly grown arrogant and thought that their monopoly meant that people would like what they tell them to like.

The independents in Hollywood based their business plan on looking for what made audiences happy and then running with it.

Soon, the old trust companies of the MPPC had crumbled into bankruptcy, and the Hollywood companies were at the top of the game.

In the 1920s the Hollywood studios had grown large, and a tad drunk on their own power. This sparked the creation of United Artists, a company founded by actors and filmmakers to produce and distribute their own films, as well as distribute the films of big name independent producers like Samuel Goldwyn, and David O. Selznick.

During the classic studio era, most independent producers were generally relegated to making low budget films for various Poverty Row companies. The Poverty Row studios specialized in "filler" material: cheap, short movies designed to fill screen time for the handful of independent cinemas that dotted the country. The main reason their market was so small was because the major studios also owned almost all the movie theatres during this era.

However, Poverty Row enjoyed a renaissance thanks to the 1949 federal consent decree that forced the studios to sell their theatres. Soon after that came the explosion of television, and studios began to cut back a lot on making their usual slate of program "filler" movies, aiming for grander and more "important" Technicolour wide-screen "A" pictures.

The newly freed theatres needed movies to show, and thanks to the post-war baby boom these films had to appeal to kids and teenagers. New companies like American International sprung up to fill this gap in the market.

Like the studios did against the MPPC, these new companies made their success by giving the public what the studios weren't. Pure entertainment that didn't claim to be important or anything else.

This system progressed through the 1960s. But things began to change. The prevalence of TV meant that movies didn't have to be everything for everybody. And the arrival of the ratings system gave filmmakers the wiggle room to push the boundaries when it came to material.

Now it was the independents that first started this. One of the most influential producer/directors of this era was Roger Corman. Seeing that the youth market was interested in edgier themes, he leaped in with both feet, making films that exploited these themes to the hilt.

The "Exploitation" Era had begun.

During its heyday in the late 60s and early 70s Corman, first through American International, and later through his own New World Company, acted as a mentor for the young filmmakers coming out of California's relatively new Film Schools. He hired them at first because they were a great source of cheap labour, but then he saw that they connected better with the youth market he sought to entertain.

Eventually, the studios, many facing bankruptcy, started to see the success of these young whippersnappers and began bringing them into the studio system.

By bringing their exploitation film mentality and marrying it with bigger studio budgets they created the era of the $100 million dollar plus Blockbuster Movie.

Now these big studio blockbusters started to squeeze the independents out of the theatres, who in the meantime were mostly swallowed up by big cinema chains. These chains only wanted big movies to attract big crowds to their new multiplex theatres.

But all was not lost.

Because home video had come along.

Home video was new, and in the early 80s small independent video stores had literally spread worse than Starbucks. These stores needed to fill their shelves with anything they could get their hands on, and the studios were a tad slow, sometimes taking years to get films out on VHS.

Home video was new, and in the early 80s small independent video stores had literally spread worse than Starbucks. These stores needed to fill their shelves with anything they could get their hands on, and the studios were a tad slow, sometimes taking years to get films out on VHS.Independent companies saw an opportunity and moved fast to exploit it. Filling video-store shelves with hundreds of low budget sci-fi, action, horror, and comedy films. Since these films needed a hook to make themselves stand out the sci-fi flicks had lots of (usually hokey) special FX, action films were more violent, the horror films had buckets of gore, and the comedies were usually low-brow sex-farces complete with topless girls and genital jokes.

Among the new crop of companies to grow in the fertile fields of VHS and begin to use their clout to get better releases for their films in theatres were New Line, New World (under new owners), Embassy Pictures, Cannon Films, Live Entertainment, and Vestron.

While Cannon dominated the low budget exploitation, producing and/or releasing hundreds of films during their run, other companies like Goldcrest, and the fledgling Miramax, sought new opportunities.

The teen market was over saturated in theatres and in video stores by both the big studios and the smaller "mini-majors." Leaving mature urban professionals under-stimulated when it came to movies.

Goldcrest and Miramax started to fill this gap. Goldcrest, sadly got overextended, and sank under its own success in the mid 1980s, but Miramax chugged along specializing in distributing foreign and "art" films to the upscale urban audience.

It was around this time also that Robert Redford started the Sundance Film Festival as a place for independent filmmakers to network with distributors and promote their films.

Then the boom hit.

New technology made film-making cheaper and a

new generation of movie brats burst onto the scene. They made films they wanted to see, and they did it faster, cheaper, and more creatively than the big studios and the ageing first generation of film school kids.

new generation of movie brats burst onto the scene. They made films they wanted to see, and they did it faster, cheaper, and more creatively than the big studios and the ageing first generation of film school kids.Sundance gave them a place to premiere their films, and companies like Miramax had the means to get them into theatres. And when these films started making money, well the race was on.

Soon the movie world was filled with Tarantino imitators and wannabe Weinsteins, and things got even worse when Tarantino's Pulp Fiction won Oscars and made over $100 million domestic gross at the box-office with a tiny budget of $8 million.

Miramax's domination of the Oscars had begun. Part of this came from shrewdly marketed quality films, but a good chunk of it came from very aggressive Academy Award campaigns that were often bigger, budget wise, than the films they were promoting.

This was when things started to go wrong.

Indie films forgot about the audiences, and aimed for Oscar wins. The big studios started buying up independent distributors. Others, hurt financially from trying to compete with the majors, went under. And Sundance became a massive corporate media-whore fest.

There was also a change in attitude. With the "indie" distributors now small cogs in massive corporate machines, the need to make films that actually appeal to audiences, even small ones, dwindled. They didn't need to make money, since their existence was to attract awards, and give the parent companies a tax-write-off.

Soon what was once challenging, became insulting, daring became offencive, and artistic became an excuse for being incoherent and obscure. Indie films went from giving the people what mainstream Hollywood wouldn't give them, to giving Hollywood what the people don't want.

And that pretty much sums it up.

No comments:

Post a Comment